I just listened to the unabridged audiobook of Steven Johnson’s The Ghost Map: The story of London’s most terrifying epidemic, and how it changed cities, science and the modern world.

I just listened to the unabridged audiobook of Steven Johnson’s The Ghost Map: The story of London’s most terrifying epidemic, and how it changed cities, science and the modern world.

It is the summer of 1854. Cholera has seized London with unprecedented intensity. A metropolis of more than 2 million people, London is just emerging as a one of the first modern cities in the world. But lacking the infrastructure necessary to support its dense population – garbage removal, clean water, sewers – the city has become the perfect breeding ground for a terrifying disease no one knows how to cure.

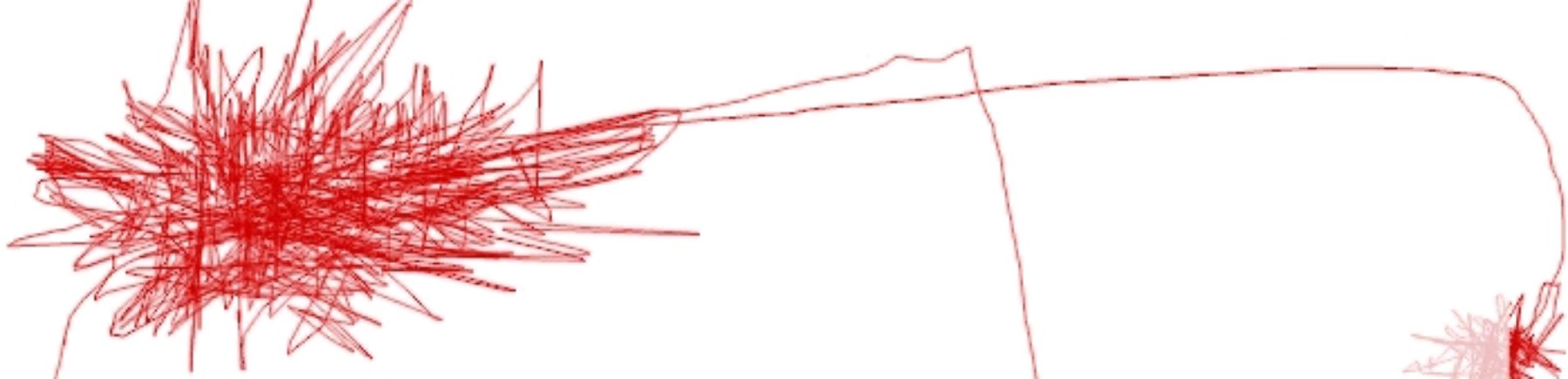

As their neighbors begin dying, two men are spurred to action: the Reverend Henry Whitehead, whose faith in a benevolent God is shaken by the seemingly random nature of the victims, and Dr. John Snow, whose ideas about contagion have been dismissed by the scientific community, but who is convinced that he knows how the disease is being transmitted. In a riveting day-by-day account, The Ghost Map chronicles the outbreak’s spread and the desperate efforts to put an end to the epidemic – and solve the most pressing medical riddle of the age.

It’s the kind of history I particularly enjoy, with lots of discussion of customs, beliefs, and real people’s lives and activities. Johnson combines that with a good mystery and well-articulated explanations of science both current and historical — it’s a very well-put-together and gripping book.

Plus, read this book and you get to have fun dinner-table exchanges like this:

Me: Did you know that in 1850s London it was so expensive to get someone to empty your cesspool that one in twenty houses didn’t bother and just let their basements fill up with poop? One in twenty!

D: Don’t ever tell me anything else from that book.

Me: What? I waited until you were done eating!

Yes, with its extensive discussions of sewers, cesspools, smells, miasmas, anaesthetic-free surgeries, and the hideous sufferings of cholera victims, this is definitely not a book to listen to while doing anything involving food or while experiencing a bout of hypochondria. Might be good for inducing urges to clean things, though.

In the last few chapters Johnson expounds at great length about modern disasters, the uses of modern technology, and how we might proceed to avoid these. It’s competently done but since the mystery mentioned in the book’s title has by this point in the book been solved, there’s no plot to hold one’s interest. This extra material — although tangentially related — feels out of place. The book would be stronger if this material were omitted, although it might make for an interesting series of shorter essays. This weaker last section certainly doesn’t ruin the very strong majority of the book, however.

Don’t you want to know all kinds of sordid details about what it’s like to live in a city of 2 million before the advent of proper sewers, public health, or anaesthesia? Of course you do. It’ll make you feel eversomuch better about your own circumstances and give you a whole new appreciation for your toilet.